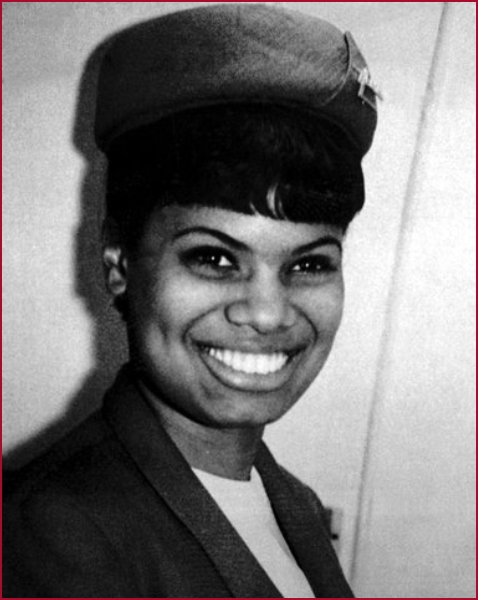

When Patricia Murphy and Phenola Culbreath first stepped onto airplanes as flight attendants in 1966, they weren’t just starting new careers — they were breaking racial barriers at 30,000 feet.

Hired by Delta Air Lines just two years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the two women became among the airline’s first Black flight attendants at a time when most carriers refused to accept Black applicants.

Today, the trailblazers are reflecting on their experiences and legacy during a visit to the Delta Flight Museum, where they shared how they endured hostility, strict workplace rules, and social isolation — while building careers that spanned more than three decades.

Facing Racism in the Cabin

Murphy recalled being the only Black flight attendant among dozens of colleagues early in her career.

“Out of 50 flight attendants, I was the only Black,” she said, describing how some passengers refused to acknowledge her presence. “Some people would turn away. They would not make eye contact with me. Of course, the name-calling. Being pushed and shoved on the airplane.”

Despite the discrimination, she said she relied on resilience and professionalism to push forward.

“With grace,” Murphy said. “Just like I handled everything else. I didn’t let that stop me from being me.”

Culbreath said seeing another Black flight attendant for the first time was an emotional moment.

“I almost fainted,” she recalled.

Barriers Beyond Race

The women also faced strict hiring requirements common in the airline industry at the time. Applicants had to be young, single, meet rigid appearance standards, and often were forced to retire by their early 30s.

These rules disproportionately affected women — especially Black women trying to enter the field.

One early pioneer, Ruth Carol Taylor, was hired by another airline but lost her job within months after violating a company marriage ban.

Murphy and Culbreath, however, defied expectations by building careers that lasted more than 35 years — a rarity in an era when many flight attendants were pushed out early.

Making History Without Realizing It

Both women said they did not initially grasp the historic significance of their roles.

“At the time when you’re living it, you don’t really think in those terms,” Murphy said. “I didn’t realize the impact historically of what it meant.”

Their story was recently revisited by reporter Najja Parker of the The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, highlighting how their perseverance helped open doors for future generations in aviation.

Lasting Legacy

Today, Murphy and Culbreath are recognized as pioneers who helped integrate the airline workforce and reshape opportunities for Black women in the industry.

Their experiences serve as a reminder of both the progress made since the Civil Rights era and the personal courage required to achieve it.