February is Black History Month, a time to celebrate the remarkable achievements of Black individuals throughout history. And within the world of dance, few stories are as inspiring as that of Janet Collins, a trailblazing ballerina who defied racial proscription and left an indelible mark on the art form.

Long before Misty Copeland became a household name, Collins was paving the way, fighting against racial discrimination at a time when Black ballerinas were routinely dismissed, underestimated, and even asked to alter their appearance to fit a Eurocentric mold.

Born in 1917, Janet Collins had a passion for ballet from an early age. But like many Black dancers in the 1930s, she was met with relentless resistance. Ballet was a field dominated by white dancers, and professionals often claimed that Black bodies were “unsuited” for the art. Collins, however, refused to be discouraged. She devoted herself to mastering the craft, determined that her talent would speak louder than her skin color.

At 15, Collins auditioned for the Lèonide Massine and De Basil Ballet Russe Company. Her performance was so breathtaking that even the other ballerinas applauded her. It seemed like a breakthrough moment—until Massine offered her a spot in the company under one humiliating condition: she would have to wear whiteface to conceal her Black identity.

This demand encapsulated the insidious racism of the era. When faced with a choice between her dream and her integrity, Janet Collins made a powerful decision. She refused. Leaving the audition in tears, she channeled her disappointment into fierce determination. From that moment forward, her driving force was clear: her talent would speak louder than her skin color.

After her audition for Lèonide Massine and the De Basil Ballet Russe Company, Janet took part in productions created by the government-supported Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. This included Hall Johnson’s Run, Little Chillun, and the 1938 Chicago production of Swing Mikado. Additionally, Janet participated in vaudeville performances while enduring the harsh rejection from the elite dance industry she wished to join. However, a significant opportunity arose in the following decade. Following a friend’s suggestion, Janet tried out for Katherine Dunham and successfully earned a place in her black dance company. She performed with the group in the 1943 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, regarded as one of the finest musicals featuring an all-black cast. Nevertheless, reflective of the racially biased era, the film includes some elements of minstrelsy, featuring Sambo representations and blackface.

Even with her accomplishments in New York, Collins encountered racism while touring in southern cities. Due to racial laws that barred her from performing, her roles were occasionally taken over by understudies, highlighting her unwavering determination to overcome such strict racial obstacles, which was remarkably brave.

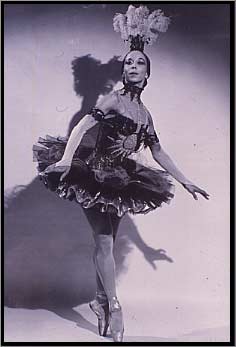

Janet Collins achieved a significant milestone by breaking a racial color barrier when she performed in a production of Aida in November 1951. The following year, she became a Met’s corps de ballet member, establishing herself as its first black prima ballerina. Her time with the Met included tours throughout the South, where she encountered racism. However, Janet continued to dance for the Met until 1954. Eventually, she dedicated herself to teaching ballet and choreographing performances.

Collins’ talent, grace, and refusal to compromise her identity made her an icon. Her journey paved the way for generations of Black dancers, proving that ballet was not reserved for one race but was an art form where talent should reign supreme.