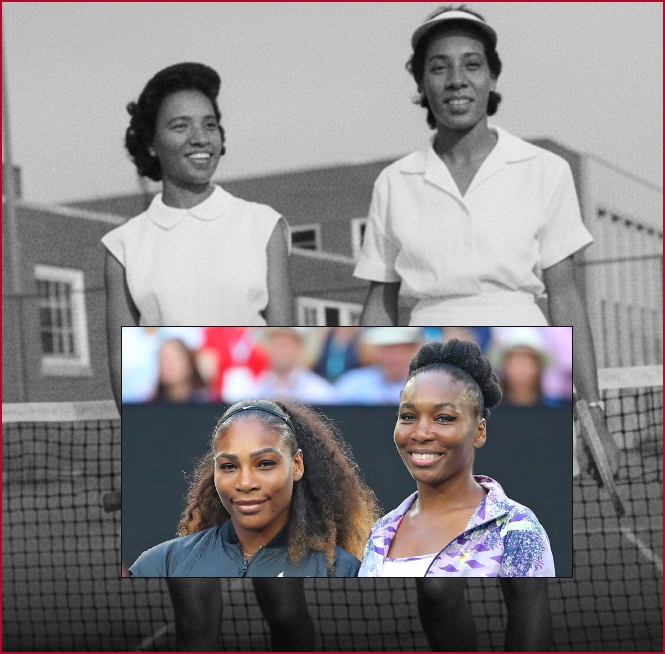

Long before Venus and Serena Williams transformed women’s tennis into a global showcase of Black excellence, two little-known sisters from Washington, D.C., were already breaking barriers on the court.

Margaret and Matilda Peters — nicknamed “Pete” and “Repeat” — rose to prominence during the era of racial segregation, dominating Black tennis circuits from the late 1930s through the early 1950s and helping lay the groundwork for future generations of athletes.

Rising Through Segregated Tennis

According to historical records from the American Tennis Association (ATA), the Peters sisters honed their skills at a time when Black athletes were barred from competing in mainstream tennis tournaments sanctioned by the United States Lawn Tennis Association, now the USTA.

Founded in 1916, the ATA became the primary competitive platform for Black tennis players shut out of white-only competitions during the Jim Crow era.

Within this system, Margaret and Matilda quickly emerged as a formidable doubles team.

ATA archives and Black sports historians credit the duo with winning 14 ATA women’s doubles championships, making them one of the most successful pairings in the association’s history.

They earned their playful nickname because of their consistent appearances together in finals — a nod to their near-identical playing styles and relentless competitive chemistry.

Style, Skill and Singles Success

Contemporary accounts from Black newspapers such as The Afro-American and Chicago Defender, which closely covered ATA tournaments at the time, describe the sisters as tactically disciplined players known for powerful backhands, sharp slice serves, and strategic court positioning.

While they dominated doubles competition, Matilda Peters also carved out an impressive singles career.

Sports historians note she won multiple ATA singles titles and at one point defeated Althea Gibson, who would later become the first Black player to win a Grand Slam title and break tennis’ color barrier internationally.

Barriers Beyond the Court

Like many Black athletes of their generation, the Peters sisters competed without financial support.

Historical accounts indicate they paid their own travel and equipment costs and received no prize money — a stark contrast to modern professional tennis.

Despite these obstacles, both sisters pursued careers in education and community service after their playing days, becoming mentors and local leaders in Washington, D.C., according to ATA historical profiles.

Legacy in Today’s Game

Sports scholars widely credit the ATA and its early champions, including the Peters sisters, with sustaining Black participation in tennis during segregation and creating a pipeline that eventually produced stars such as Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, and later the Williams sisters.

Their story remains largely unknown outside historical tennis circles, yet experts say their impact is profound.

“They proved Black women belonged in tennis long before the world was ready to accept it,” ATA historical commentary notes.

Today, as conversations about representation in sports continue, historians say the legacy of Margaret and Matilda Peters underscores how progress in tennis was built on decades of overlooked pioneers.

They did not just compete in the sport — they helped open its doors.