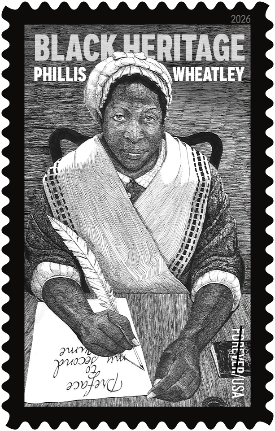

As we mark Black History Month, it’s fitting to celebrate the life and legacy of Phillis Wheatley, one of the earliest and most remarkable voices in American literature.

Wheatley was a woman whose talent and perseverance helped redefine what Black artistic achievement could look like in the 18th century.

Born around 1753 in West Africa, Phillis Wheatley was captured as a child and transported across the Atlantic to Boston, Massachusetts, where she was sold into slavery in 1761. Her enslavers, John and Susanna Wheatley, recognized a remarkable intellect in the young girl and began teaching her to read and write — an extraordinary opportunity for an enslaved person at the time. In less than two years, she had mastered English and moved on to study Latin, Greek, the Bible, and British classics.

By her early teens, Wheatley was already writing poetry, and in 1767 she had her first work published in a Newport, Rhode Island newspaper. But it was her elegy on the death of the evangelist George Whitefield, published in 1770, that brought her widespread recognition in the colonies.

A Groundbreaking Book and Global Recognition

In 1773, Wheatley’s book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral became the first volume of poetry published by an African American, and one of the earliest books by a woman in what would become the United States. Because many American publishers were reluctant to publish work by an enslaved Black woman, the volume was first printed in London, where she was celebrated by literary figures and abolitionist supporters.

Her poems often blended classical poetic forms with personal experiences and spiritual reflection. In “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” Wheatley not only shares her spiritual journey but challenges prevailing prejudices by asserting that Africans, too, could be “refin’d and join th’ angelic train.”

Wheatley’s work drew praise from notable figures of her time. After she wrote a flattering poem honoring George Washington, the future president replied with praise and invited her to visit him — a rare cross-cultural exchange in the era of the American Revolution.

Freedom, Struggle, and Legacy

Shortly after returning from London, Phillis Wheatley was manumitted (freed from slavery). She continued to write, married a free Black man, and attempted to support herself and her family through her poetry. Despite her early fame, she faced the harsh realities of a society that offered few opportunities for Black writers; publication opportunities were limited, and she died in relative obscurity in Boston in 1784 at about 31 years old.

Nevertheless, her legacy lives on. Wheatley’s work not only broke racial and gender barriers but also challenged assumptions about Black intellectual and artistic achievement at a time when such recognition was rare or resisted. Her poetry became a powerful symbol for early abolitionist arguments and has inspired generations of writers, scholars, and activists since.

As we honor Phillis Wheatley this Black History Month, we remember her not just as a historical figure but as a literary pioneer whose voice helped shape the early cultural landscape of America and whose courage and creativity continue to resonate more than two centuries later.