In 1915, at just 23 years old, Alice Augusta Ball made a groundbreaking scientific breakthrough that changed the treatment of leprosy forever.

Yet, for decades, her name was nearly erased from history. Ball, a brilliant African American chemist, developed the first effective injectable treatment for leprosy, a disease that had forced thousands into exile.

Her work provided hope and healing, but a white male colleague stole the credit, rebranding it as his own. More than a century later, her legacy is finally being recognized, ensuring that her contributions to medicine will never be forgotten.

A Scientific Prodigy

Born in Seattle, Washington, in 1892, Alice Ball was raised in a family that valued education and innovation. Her father, James Presley Ball Jr., was a newspaper editor and lawyer, and her grandfather, James Ball Sr., was a pioneering photographer.

Encouraged by her family’s intellectual environment, Ball excelled in science from a young age. She attended the University of Washington, where she earned degrees in pharmaceutical chemistry and pharmacy before pursuing a master’s in chemistry at the University of Hawaii.

She became the first African American and the first woman to earn a master’s degree from the university and was later hired as a chemistry professor—the first Black woman to hold such a position.

The Breakthrough That Changed Leprosy Treatment

At the time, leprosy—also known as Hansen’s disease—was a devastating illness with no reliable cure. Patients were often forcibly removed from society and sent to live in isolation, particularly in Hawaii, where many were exiled to the remote island of Molokai.

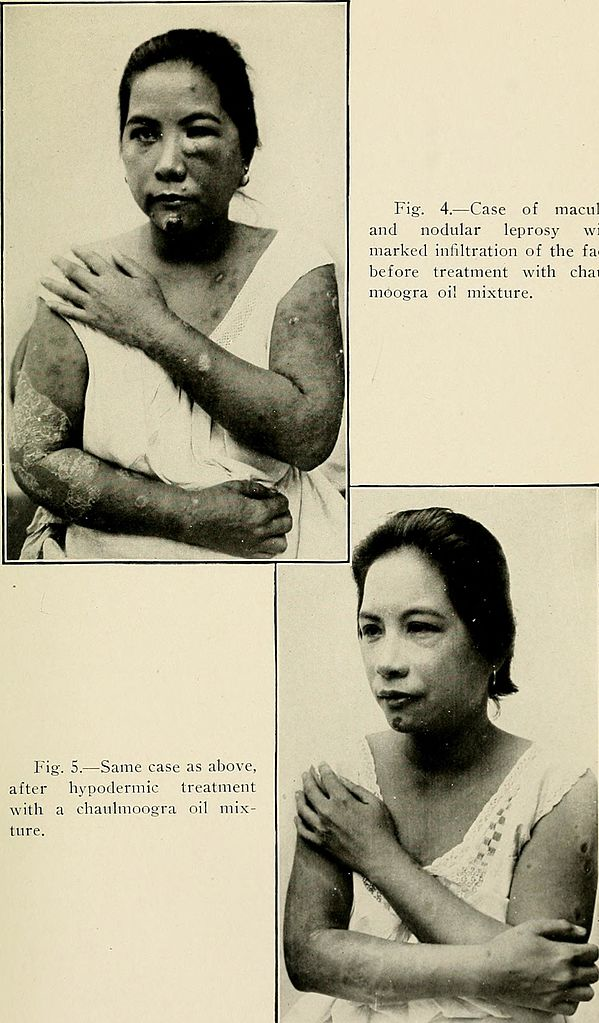

While chaulmoogra oil had long been used in traditional medicine to treat leprosy, it was largely ineffective in its natural form. The oil was too thick to be absorbed when applied topically, too bitter to be ingested, and too viscous to inject properly.

Under the guidance of Dr. Harry T. Hollmann, Ball dedicated her research to solving this problem. She developed a groundbreaking method to chemically modify chaulmoogra oil, making it water-soluble and injectable, allowing it to be easily absorbed into the bloodstream.

This revolutionary discovery, later known as the “Ball Method,” became the first practical treatment for leprosy, liberating patients from exile and offering them a chance at a normal life. Her innovation was widely used until the 1940s, when sulfone drugs replaced it.

Stolen Credit and the Fight for Recognition

Despite the magnitude of her achievement, Alice Ball did not live to see the full impact of her work. She tragically passed away in 1916 at the young age of 24.

Shortly after her death, Arthur L. Dean, the president of the University of Hawaii, took credit for her discovery, renaming it the “Dean Method” and erasing Ball’s name from the medical breakthrough she had pioneered. It was not until years later that Dr. Hollmann publicly spoke out, crediting Ball for her revolutionary work.

For decades, Ball’s contributions were largely overlooked. It wasn’t until 2000—nearly 85 years after her passing—that the University of Hawaii honored her legacy by placing a plaque on campus near the only chaulmoogra tree.

In 2007, she was posthumously awarded the university’s Medal of Distinction, and February 29 was officially declared “Alice Ball Day” in Hawaii. Today, Ball is celebrated as a pioneer in medicine and chemistry, with her contributions finally receiving the recognition they deserve.

A Legacy That Endures

Alice Ball’s life was short, but her impact on medicine was profound.

Her innovative research provided effective treatment for a disease that had plagued humanity for centuries, and her story stands as a testament to the brilliance of Black women in science—whose contributions have too often been ignored or erased. Today, her name is remembered in medical textbooks, historical accounts, and classrooms worldwide.

Alice Ball’s legacy serves as a powerful reminder: No matter how history tries to erase them, the achievements of Black women in science will always shine through.