Before it was common for women, let alone Black and Native women, to be recognized as fine artists, Edmonia Lewis carved a place for herself in history, literally and figuratively.

The daughter of a Black father and a Chippewa (Ojibwa) mother, Lewis rose from tragedy and discrimination to become the first sculptor of African American and Native American descent to gain international acclaim.

Born in 1844 and orphaned at a young age, Lewis was raised among her mother’s tribe in upstate New York. Her early life was steeped in nature, craft, and survival.

She spent her childhood fishing, swimming, and creating handmade goods — the first stirrings of what would become her lifelong dedication to artistry.

In 1859, Lewis enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio, one of the few institutions at the time that welcomed Black and female students. But her studies were derailed after she was falsely accused of poisoning two white classmates, a charge many believe was racially motivated. Though acquitted, the damage to her reputation forced her to leave school without graduating.

What could have ended a young woman’s dreams instead forged a fire inside Lewis. That fire grew when she encountered a sculpture of Benjamin Franklin in 1864. She didn’t have a word for what she was feeling, but she knew — instinctively — that she was called to sculpt.

Denied apprenticeships again and again, Lewis finally found a mentor in Edward Augustus Brackett, a well-known abolitionist sculptor in Boston. Under his guidance, Lewis began crafting marble busts of white abolitionists like John Brown, Charles Sumner, and William Story. But commissions were scarce, and America’s deep-seated racism made her artistic journey uphill every step of the way.

Still, Lewis refused to be silenced. During the Civil War, she joined the Underground Railroad and helped organize one of the first Black Union regiments. She fought for freedom on every front — in the studio, in politics, and in her community.

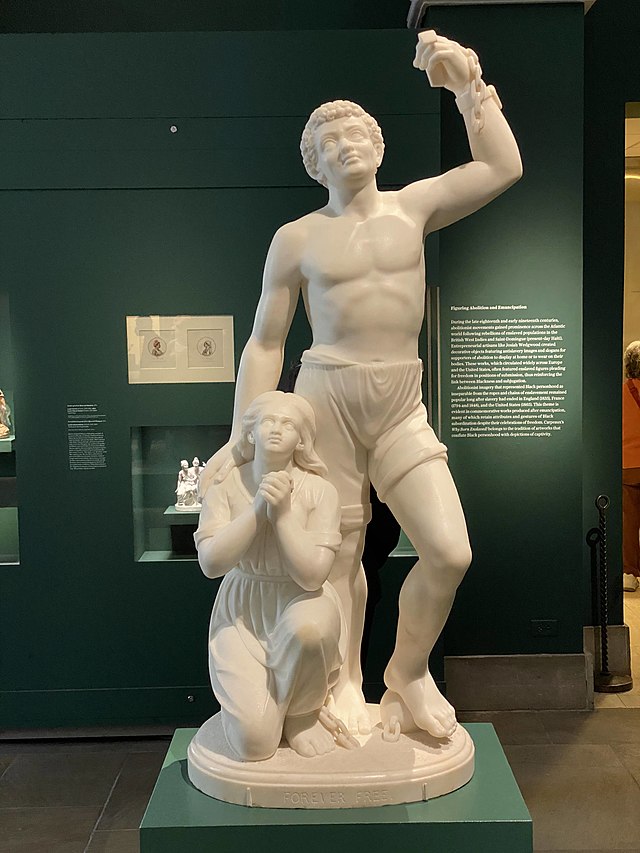

Her most celebrated work, “Forever Free” (1867), remains a powerful visual declaration of emancipation. The sculpture, which depicts a formerly enslaved man and woman in the moment of liberation, blends deep emotion with quiet strength. One hand raised in triumph, the other protectively draped around his partner — it is a masterclass in storytelling through stone.

By 1865, Lewis moved to Rome, a city where she could be judged for her talent rather than her race or gender. She joined a circle of American women sculptors in Italy, but unlike most of them, Lewis insisted on carving her own marble. She feared that if others touched her work, critics would not believe she was the true artist.

And in many ways, she was right to worry. As a Black and Indigenous woman in a white-dominated art world, Lewis faced continual doubt and discrimination. But in Rome, she found both freedom and appreciation. Her studio attracted international attention, and she remained in Italy for the rest of her life, carving a legacy that outlived her.

A student who once wrote a college paper on “Forever Free” in 1982 summed up Lewis’ influence with the phrase: “Go where you’re celebrated, not tolerated.” It’s a sentiment that defines Edmonia Lewis’ story. She didn’t ask permission — she claimed her space in the world.

Today, her sculptures are housed in the Smithsonian, the Howard University Gallery of Art, and private collections around the globe. Her life continues to inspire new generations of artists, historians, and freedom fighters.

Edmonia Lewis didn’t just make art — she made history.