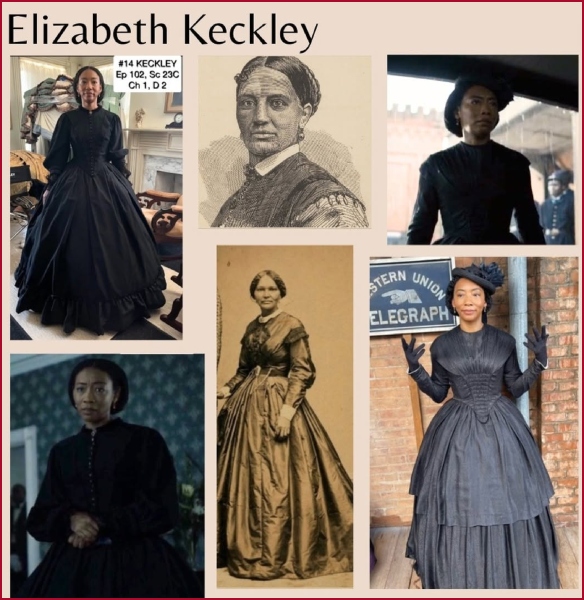

During Black History Month, stories of resistance often focus on protests, revolts, and legislation. But Elizabeth Keckley’s life tells a different — and equally powerful — story: one of economic brilliance forged inside an unjust system designed to deny her ownership, wages, and freedom.

Born enslaved in Virginia in 1818, Keckley was trained as a seamstress at a young age after her enslaver forced her mother to work to support his household. When Elizabeth became old enough, she took over the labor herself to spare her mother — a decision that would unknowingly launch one of the most remarkable entrepreneurial journeys in American history.

Keckley’s early skill was undeniable. Her enslaver sent her to work in a dress shop, where her craftsmanship quickly earned her a strong reputation among elite white women. According to Keckley’s own 1868 memoir, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, she generated enough income through sewing to support 17 people, even though she was legally barred from keeping a single dollar she earned.

Despite running what functioned as a business, all profits belonged to those who enslaved her.

When Keckley asked to purchase freedom for herself and her son, she was given what seemed like an impossible price: $1,200 — roughly $45,000 in today’s dollars. What her enslavers did not anticipate was the depth of the professional relationships she had built. Her clients — women who trusted her skill and depended on her labor — pooled their own money and loaned her the funds. In 1855, Elizabeth Keckley legally bought her freedom.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture confirms this extraordinary transaction and recognises Keckley as a pioneering Black entrepreneur whose career bridged slavery and post-emancipation economic independence.

Once free, Keckley moved to Washington, D.C., where her career accelerated. She established a luxury dressmaking business that catered to the wives of politicians, generals, and diplomats. At its height, her operation employed approximately 20 seamstresses, a notable scale for any 19th-century fashion house — let alone one owned by a formerly enslaved Black woman.

Her most famous client was Mary Todd Lincoln, the wife of President Abraham Lincoln. The National Park Service and White House Historical Association both document Keckley as Mrs. Lincoln’s primary dressmaker and close confidante during the Civil War years.

Keckley’s proximity to political power also made her a cultural witness. Her memoir — controversial at the time — provided rare insight into White House life from the perspective of a Black woman, which contributed to her later marginalisation in mainstream historical narratives.

Fashion historians now recognise Keckley as one of America’s earliest couture-level designers. Institutions such as the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) cite her work in studies of early American fashion systems and Black economic innovation.

Although exact financial records from the era are limited, historians estimate that Keckley’s business — based on elite clientele, staffing levels, and garment pricing — would be equivalent to a seven-figure enterprise in modern terms, placing her among the earliest Black women millionaires by today’s standards.

Keckley’s legacy challenges long-standing myths about enslaved people lacking business acumen or strategic intelligence. Her story shows that even within extreme oppression, Black women created value, leveraged relationships, and built systems of survival and success.

Elizabeth Keckley did not merely sew dresses. She stitched together freedom, economic independence, and a legacy history nearly erased.