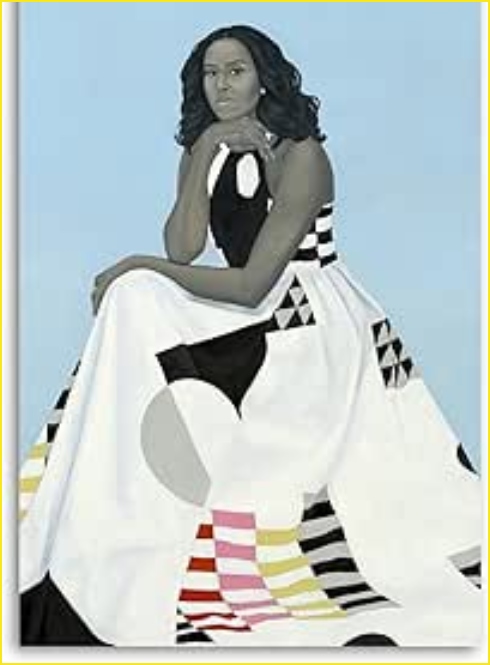

When Amy Sherald, the artist who painted Michelle Obama’s iconic portrait, pulled her blockbuster American Sublime retrospective from the Smithsonian this summer, it wasn’t a scheduling issue. It was a stand against censorship.

The celebrated painter, known for her cool composure and grayscale portraits of Black Americans, made a decision that shocked the art world. Just weeks before opening night, she canceled her own exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery — the same institution that had once made her a household name.

The reason? A quiet battle over artistic freedom that cut straight to the soul of American democracy.

A Clash Between Art and Power

Sherald, 52, says the Smithsonian, under mounting political pressure from the Trump administration, wanted to “contextualize” one of her most provocative works, Trans Forming Liberty, a portrait of a transgender person dressed as the Statue of Liberty.

Museum officials proposed showing the painting alongside a video meant to “explain” it. To Sherald, the implication was clear: her art needed translation, or worse, dilution, for a national audience.

“Any kind of contextualization around the work would have been unacceptable,” she told 60 Minutes. “It would’ve deviated from how the work was originally conceived. And because of that, I felt like my only choice was to pull out.”

The Trump White House applauded her withdrawal.

A senior official said the painting “sought to reinterpret one of our nation’s most sacred symbols through a divisive and ideological lens.”

But what Sherald saw wasn’t division — it was America. Her America.

“It lives in the world,” she said of her art. “And therefore, it can be art on Monday and political on Tuesday.”

“I’m the Definition of an American”

When Anderson Cooper asked Sherald if she considered herself patriotic, she didn’t hesitate.

“Yes,” she said. “I don’t think there’s anybody more patriotic than a Black person.”

Her reasoning was as profound as it was unapologetic:

“We’ve been here since the inception of this idea of what American is. We are deeply ingrained in the fabric of this country. This country would not be if it was not for us. So I have to claim that patriotism. Otherwise, I’m just handing it over to somebody else to give me the definition of what it means to be American. But I know what the definition is. I’m the definition of an American.”

For Sherald, patriotism isn’t waving a flag. It’s telling the truth — even when that truth is uncomfortable.

A Life Built on Defiance and Survival

Born in Columbus, Georgia, Sherald grew up under the watchful eye of parents who hoped she’d become a doctor. But one childhood trip to a local museum changed everything.

She saw a painting of a Black man, the first she’d ever encountered in art, and decided she’d dedicate her life to painting people who looked like her.

It wasn’t an easy road. Sherald waited tables for more than a decade to support her art, often wondering if anyone would ever notice her work.

Then, in 2004, life stopped her cold. A rare heart condition threatened to kill her if her pulse climbed too high. After collapsing in 2012, she received a life-saving heart transplant at age 39. Her donor was a young woman named Kristin Lin Smith — whose name Sherald still writes into her life story.

“Whenever I do something I couldn’t have done before, I hashtag it #adventuresofKristinandAmy,” she said. “And when I sign my name, I put a little heart on the end for her.”

The Crime of Contextualization

In a sense, what happened to Sherald at the Smithsonian is part of a larger American crime, the institutional policing of artistic voices that dare to redefine the national narrative.

By suggesting her work required “context,” the Smithsonian crossed into a dangerous territory: soft censorship. It’s the kind that doesn’t burn books or tear down canvases, it simply reframes them until their meaning is stripped away.

And Sherald refused to let that happen.

In her world, freedom of expression isn’t negotiable. Art must provoke, not appease.

The Politics of Grayscale

What sets Sherald’s paintings apart — beyond their luminosity and quiet power — is her use of grayscale skin tones. Her subjects are unmistakably Black, yet rendered in shades of gray, blurring the viewer’s assumptions about identity.

“It offers the viewer an opportunity to pause and consider something else before we get to that,” she said. “They look Black. I can’t take Blackness away from them. But the lack of color allows for a different entry point.”

In that artistic decision lies a profound commentary: race can be seen, but it doesn’t have to define humanity.

Freedom Reclaimed

After the Smithsonian debacle, Sherald didn’t fade. The Baltimore Museum of Art stepped in, offering to host American Sublime — opening Nov. 2. What the federal museum tried to sanitize, Baltimore chose to celebrate.

For Sherald, the move was symbolic. Art, much like democracy, survives through reinvention.

And for an artist whose very existence is a testimony to resilience, the Baltimore opening isn’t just an exhibition. It’s vindication.

“It’s technically what I wanted,” she said. “As a Black woman artist, American, for people to say, ‘Amy Sherald, Norman Rockwell, Edward Hopper.’ I’m in the room with the guys. And I’m OK with that.”

Why It Matters

Sherald’s story is about more than a canceled show. It’s about the ongoing collision between truth and control, and how easily institutions can falter when faced with both.

Her quiet defiance exposed a truth few are willing to confront: censorship in America doesn’t always wear a uniform or wield a ban. Sometimes, it wears a smile and asks to “contextualize” your art.

And in standing her ground, Amy Sherald did what true patriots do: she protected the essence of freedom itself